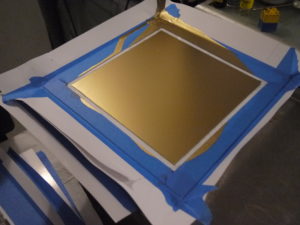

I usually make about 20 prints onto glass before laying on the “gold” (or whatever) covering.

Happily for me, I find just about all of the stages of making a final image with creative processes a pleasure. From being in the total dark for up to half an hour in lith printing waiting to guess the exact second I must whip out the invisible print and stop development, to boiling down concentrated nitric acid with a gas mask and protective rubber suit in the garden to make silver nitrate.

Varnishing orotones (or my new chromotones) is clean, quick and simple. Sort of. I can be very messy and get complicated if everyting is not laid out and ready.

I suppose an “orotone”, by definition, has a dense reflective gold finish. The colour of pure 24ct gold is, well, “gold”. But to find a powder to make into a perfect emulsion can be tricky. Commercial powders and pigments come in a huge range of colours claiming to be gold. The orotone today owes a lot to Edward Curtis. Curtis employed a good team, including some Japanese craftsmen, to produce the orotones, which he promoted as Curt-tones. By 1916 he was selling popular prints from his Native American series for very good (high) prices. The exact formulas and techniques varied a lot and developed over 20 years or more. I have not found any reference to Curtis using real gold.

I have tried many metallic powders, like Curtis I have found that a brass powder works well. There are many proportions which can be used for of the main ingredients, copper and zinc to make brass – it can be produced in many different colours. I have tried to find a mixture which is as close to pure 24ct gold as possible.

The size of the powder is important. I have tried to make pigments and powders myself, but to get the powder to the fine-ness (is there such a word?) I like seemed difficult, but some commercial suppliers do sell exactly what works for a much lower price than making it myself.

The main binder the Curtis used for his golden varnish was banana oil (amyl acetate) I like this, it smells of making model aircraft and old sweet shops, but other components like lavender oil and benzine were used by Curtis. As I am working more then 100 years after Curtis, I have the advantage of learning about modern archival varnishes. For me the best is the commercial product, Paraloid B72

I make the varnish in toluene dissolving 100 grams per litre of toluene. This varnish is used in museums for fossils and many other archival purposes, so it is good enough for archival photographs.